« Dialogues for a New Millennium

Interview with Nat Muller

“I am extremely weary of the instrumentalization of the arts for social or political change, as it usually produces mediocre art.”

Dutch Nat Muller is a curator based in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. With a background in literature, she ended up, via a detour, specializing in contemporary art and media in the Middle East. Some of her most recent projects include “Memory Material” at Gallery Akinci (Amsterdam), ”Customs Made: Quotidian Practices & Everyday Rituals” at Maraya Art Centre in Sharjah (UAE), and ”This is the Time. And this is the Record of the Time“ at the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam and the American University of Beirut Art Galleries. We discussed her relationship with the artistic scene in the Middle East, the complex relationship between art and politics, and the current hype surrounding art in the Gulf countries.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán - Let’s begin with your professional profile. You’ve studied literature. How did you end up in the art world?

Nat Muller - By an expanded curiosity, followed by coincidences and not so unlikely diversions. I studied literature with a specialization in feminist literary criticism and queer theory. This was in the mid-1990s-you know the advent of ‘www’-and there was this very exciting thing called cyber-feminism that was the next hottest thing on the block. Here was a feminism that reformulated the emancipatory project as primarily a technological and hands-on one. It was about rewriting women in technological and scientific histories but also proving that tech toys were not solely for boys. Many of cyber-feminism’s most vocal advocates were artists and cultural practitioners such as Faith Wilding, Kathy Rae Huffman, Shu Lea Cheang, the German Old Boys Network and the brilliant Australian collective VNS Matrix, with its cyber-feminist manifesto for the 21st century. How can you resist a line like “We are the virus of the new world order disorder, rupturing the symbolic from within, saboteurs of big daddy mainframe.” It was geeky but sexy and had an incredible sense of agency, DIY and possibility about it. Of course, much of it had to do with that particular momentum and the enthusiasm and naivety we had about the advent of the Internet and its democratizing potential. To make a long story short, I obsessively started frequenting new media exhibitions and events, subscribed to mailing lists, etc., and started working for a now defunct organization concerned with technology, art and gender, and that was basically my entry point.

P.B. - You’re especially known for your focus on art and media from the MENASA region (Middle East North Africa South Asia) or Middle East. How did this come about?

N.M. - I have always been interested in issues of power and difference because of my own mixed background (Jewish-Indonesian). In 2002, during the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, I saw Palestinian filmmaker Azza El-Hassan’s film News Time, a personal narrative on the impact of the second intifada on everyday life, but also on the difficulties and possibilities of filmmaking under siege. This film really brought to the fore how the sociopolitical condition of a place influences aesthetics, format, content. Moreover, it also begged a scrutiny of the dynamics of representation and perception: How indeed can artists go beyond generic news images or narratives, and what is the role of media and technology within such an endeavor? This work really shook me up in a profound way. The co-relations between politics, media, context and aesthetics examined in her work became somewhat of an obsession, and I wondered what type of work was produced elsewhere in the region of the Middle East. What counter-tactics do artists use in order to turn around the media image, or how can they have media work for them and with them, for the sake of remembrance or accounting narratives of a different kind? I wrote a research proposal, got some money, started traveling to and working in the region-predominantly Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt-and never looked back.

P.B. - The art world doesn’t believe in national narratives and claims it’s a global fraternization. Nevertheless, time and again it looks for new markets and new audiences-China, Russia, Brazil. Has the Middle East become the next big hot issue?

N.M. - I would disagree with you that the art world doesn’t believe in national narratives. Globalized as it may be, there are still plenty of geographical survey and country shows around. In addition, artists hailing from places under pressure (politically, socially, economical or other), as, for example, the MENASA region, are treated differently than their Western peers. Often they are pushed into a role of becoming spokespeople for their societies and their work ends up being read solely through a sociopolitical lens. When the work is complex or does something else then the authenticity card is still played and dealt unfairly. Expectations are thus very different in the so-called globalized art world you sketch out. It seems to me that a gradual curatorial interest in the Middle East started about a decade ago. The aftermath of 9/11 and the Iraqi invasion, but surely also Catherine David’s Contemporary Arab Representations project probably being main catalysts. The past few years, artists from the region have been pretty well represented in international events, biennials and certainly in the last Documenta. The Sharjah Biennial and Istanbul Biennial have become international art events to reckon with, and an increasing institutionalization and professionalization of the art scenes in the region have drawn more international curators to visit and have furthered collaborative projects with the region. I would say that institutional interests (as opposed to the individual initiatives of curators) and the markets really shifted with the movement of capital from north to south, the global economic crisis, the inauguration of the art fairs in the UAE, Art Dubai (2006) and Abu Dhabi Art (2008), and the aggressive (and at times ill-conceived) investments and mega projects in arts and culture particularly in Abu Dhabi and Doha. These have all contributed to a heightened interest that is not all necessarily content-based. We have passed the stage of the Middle East being the next hottest thing. Saudi artists are all the rage now, fueled partly by an inflated market and, well, this exotic idea that there’s actually contemporary art coming out of a place like Saudi Arabia.

PLACES OF PRODUCTION VERSUS PLACES OF CONSUMPTION

P.B. - When we try to map a big, complex, contradictory region in terms of history, aesthetics and politics like the Middle East, it is very easy to fall into clichés or reductive descriptions. Nevertheless, sometimes these can be very useful. Could we establish two main blocks when codifying the artistic practices from this region? On the one hand, places like Lebanon, Egypt and Palestine where there has been some artistic tradition (both institutional and alternative), and the more recent Gulf states more focused on the market. If you agree, could you elaborate a bit first on the traditional places of art production and its idiosyncrasies?

N.M. - Places like Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt and before the war also Iraq and Syria are places of intellectual and artistic production. And while everyone has been very focused on contemporary art, these places have rich modernist art histories, which now, it seems, are being rediscovered, researched and shown not the least in Doha’s Mathaf (the Arab Museum of Modern Art), which is largely dedicated to showing modern Arab art. This is a very good thing to see. There are, of course, huge differences in how these respective art scenes have developed over time and how national, regional and global social and political contexts (e.g. the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine, the Lebanese civil war and its aftermath, the hope and failures of the Arab Spring, the war in Iraq, Syria, etc), have impacted on certain practices. Another factor is artists living and working in the diaspora or in exile, but who still have strong connections to their home country. It is impossible to generalize, but recurring themes are memory (individual and collective), loss, identity and representation, the production and construction of history, the thin lines between truth and fiction, the countering of stereotypes (disorientalization), the archival, relations to increasing and rapid urbanization and globalization, a critique on institutionalization and the expectations of the art world, etc. However, many artists also make works that do not fall into these categories at all, and that’s again a good thing.

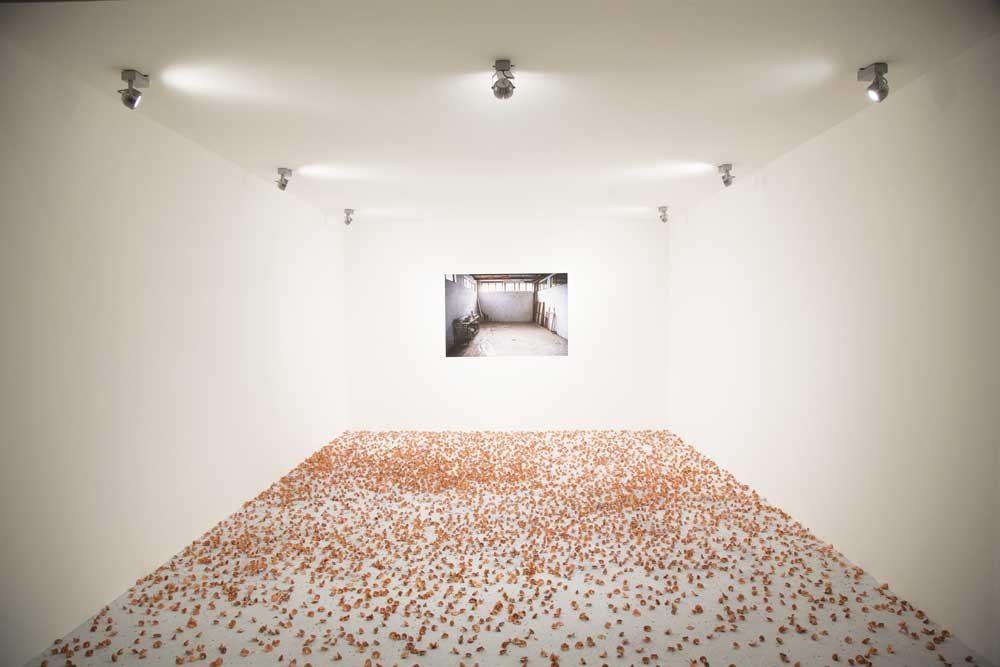

Taysir Batniji, Hannoun (1972-2009). Colour photography on paper 150 x 100 cm and pencil shavings (variable dimensions). Installation view of “Customs Made: Quotidian Practices and Everyday Rituals,” curated by Nat Muller and Livia Alexander. Maraya Art Centre, Sharjah (March 12 – May 12, 2014). Courtesy of Nat Muller.

P.B. - And the Gulf?

N.M. - I would not say the Gulf is only focused on the art market, though there is a growing collector base, and since 2007 galleries have mushroomed in Dubai. The art market elsewhere in the GCC is nascent. Tiny Qatar (its royal family) spends over $1 billion on art annually, but that is a very different dynamic. There are large differences across the GCC, even in the UAE, in how investment in arts and culture is played out: from the contested international city branding and prestige projects of the Louvre and Guggenheim in Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi, the commercial scene in Dubai, to the Sharjah Art Foundation and its biennial (notably one of the only organizations actually funding regional production). And then there is Qatar with its Islamic museum, the Mathaf, and the ostentatious (and very expensive) projects of superstars such as Damien Hirst, Richard Serra, etc. We have to remember though that, despite their wealth, countries in the GCC remain conservative, tribal and autocratic. Questions about audiences and sustainability need to be asked, and in a context where censorship and clampdowns on freedom of expression are rife, especially since the so-called Arab Spring, one needs to remain critical of how progressive these developments really are.

THE GULF AND THE WESTERN ART WORLD: A PRAGMATIC RELATIONSHIP

P.B. - I think that’s precisely the point: What is the attitude of the art world? Important institutions like the Louvre and Guggenheim, relevant curators like Catherine David, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, artists like Hirst and Serra, auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s-practically every one is participating without any objection whatsoever. Are we naïve or just hypocritical?

N.M. - Well, that is a question you should pose to them. With major cuts in public funding for the arts in Europe due to the economic global crisis and right-wing populism in Europe I can understand that Western institutions are courting the Gulf and seeking out opportunities there, just as much as other industries are doing worldwide. There is, of course, a problem in doing this in a celebratory and uncritical way and ignoring the context and political realities of these places, especially since the art world is full of progressive political discourse. Maybe our expectations of the ethical stance of the art world are too high to start with anyway. I have no qualms about the motivations of the decision makers in the Gulf and the boards of large Western art and academic institutions. The question, though, is whether this relation is sustainable and at what price it may come (curbs on freedom of expression, dire migrant labor rights, effects on collection and curatorial strategies due to censorship, effects on the academic curriculum, etc). As long as the interest is mutually beneficial, and as long as the initiatives in the GCC obtain validation through prestigious Western institutes and star curators and the institutes in the West in return receive much-needed petro-dollars, it might. For auction houses it is a viable and exciting new market where people have money to spend, so that makes sense to me.

P.B. - I guess you are right. It’s a complex situation, but when I see all these authoritarian tribal monarchies from the Gulf spending so much money on art while we find terrible censorship, a lack of freedom of speech and freedom of press, and even inhumane working situations (see Guggenheim and Louvre), I can’t help but think of the ideological use MoMA and the CIA did with Abstract Expressionism and Pollock or Franco with Informalism and Tàpies back in the 1950s; in other words, a rather unambiguous and far from innocent ideological use of art that promotes a positive, optimistic and progressive discourse that tells once again a fascinating story of how art and culture is being corrupted by power.

N.M. - Well, I think it is more pragmatic on the one hand and more diversified on the other hand. The CIA’s mingling did produce some interesting currents in artistic practice in the U.S., whether it was steered or not. That is not necessarily happening in the Gulf because there is little local artistic production, so works and talent are imported either from the region or internationally with an already established aesthetic or thematics. We need to, again, differentiate between projects and initiatives. The Saadiyat Island project with its Louvre and Guggenheim can be garnered under city branding and tourist promotion for Abu Dhabi; it is also an extension of foreign policy through soft power. In Doha, the beautiful Museum of Islamic Art makes sense to me; the monster retrospectives of Murakami (of course, with all the sexy stuff taken out) and others that hardly attract an audience after the opening, don’t. It’s difficult to use the discourse of contemporary art as a marker of modernity when you keep on jailing people for a slightly critical tweet, ban every voice of dissent or jail your poets (as in the case of Qatari poet Mohamed Rashid al-Ajami). The Sharjah Art Foundation does invest in the production of artwork in the region where there is a dearth of funding (public or private) for the production of work. One would hope that there would be more initiatives coming out of the GCC supporting the production of work from the region, but that would mean taking a step back, setting eyes on a longer and less flashy course. It would be a different type of long-term investment in the region, and not one of scale and bling.

CENSORSHIP AND THE LACK OF PUBLIC DEBATE

P.B. - Censorship in the art world is everywhere, perhaps more subtle in the West, or we just apply our own self-censorship. In general, exhibitions that deal with religion, gender, women’s emancipation, sexuality and the political, id est, the questioning of the status quo, are difficult in the Gulf countries. Remember the sacking of Jack Persekian in 2011 at the Sharjah Biennial because of a work by Benfodil? How is your experience in terms of art and the challenging of the established order in this area?

N.M. - Censorship might be everywhere, but there is a huge difference in degree and kind. The big difference with censorship in the arts in Europe or the U.S. and in the Gulf is that in the U.S. or Europe a public debate will usually follow, whether in the newspapers, the art press or even in other art institutions. The case of David Wojnarowicz and the Smithsonian is a good example here. There are also examples where institutions have refused to buckle under political or other pressure and have stood by their artists, as was the case with Palestinian photographer Ahlam Shibli at Jeu de Paume. This is not the case in the Gulf. A debate is close to impossible. Exhibitions have been closed down, art projects have been removed following angry tweets of the public. The Benfodil case you cite is one, the recent sculpture of French footballer Zinedine Zidane by sculptor Adel Abdessemed on the Corniche in Doha is another. Art will please, surprise, soothe, dismay or be abrasive, and you have to allow it to do so. You cannot remove everything the moment a member of the public gets upset, takes offense or dislikes something. Can you imagine? Our museums and art institutions will be empty! Rather than embracing it as a great opportunity for a dialogue, the ‘problem’ is excised. Then again, it is also a question of mentality. A few years ago I was on an art and censorship panel for the BBC’s Doha Debates. Many members of the audience expressed being very comfortable with their governments deciding for them what they can or cannot be exposed to. Of course, whether this is for TV only or whether this is what people really think is debatable, but still. In addition, there is a big difference between doing something under the patronage of the government (and most is owned by the government in the GCC) or doing something for a commercial gallery. At a commercial gallery you can get away with much more in terms of nudity or political commentary. It seems, though, that everything that touches on the Arab Spring is pretty much a no-no for everyone.

Adel Abidin, Behind the Scene (2013). This work will be on view at his solo exhibition “I love to love…,” curated by Nat Muller. Forum Box, Helsinki (FI) (November 1 – 24, 2014). Courtesy of the artist.

P.B. - Finally, it’s very difficult for artists to navigate and negotiate political situations and media representations. In this sense, I see clear correspondences with many artists in Latin America. Can art be a catalyst for social change? What can art do from a political and social point of view in the region?

N.M. - I’m extremely weary of the instrumentalization of the arts for social or political change, as it usually produces mediocre art with a very short expiration date. Art operates on a variety of registers, and if we place artists solely in the role of political and social commentators we are limiting the production of meaning. We risk neglecting affect, aesthetics, fantasy, delight and the imaginary as powerful instruments of critique. Also, art does different things in different places at different times. For example, in the 1990s and early 2000s, Lebanese artists were the ones cobbling together individual and collective narratives of the civil war in the absence of an official account and a persistent amnesia in the national psyche. In Palestine (and its diaspora), there are artists like Larissa Sansour, Khaled Hourani, Sharif Waked and Khalil Rabah who refuse to be pigeonholed either as victim or terrorist and carve out different imaginaries and articulations of agency within the Palestinian context. In Egypt, there is a flurry of creative activity, even though the last few years have been bloody, depressing and exhausting and there’s a return to a military dictatorship. For all the positive notes, artists and filmmakers have been arrested, and the climate of tolerance is definitely shrinking. But a certain energy or agency has been unleashed. In the Gulf, especially the UAE and Qatar, where the native population is massively outnumbered by expats (often the native population is less than 15 percent) but where the nationals hold all the rights and privileges, there is a lot of work to be done in terms of audience building and education and pacing the mentality of the place with the type of projects.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York and recently curated “The End of History…and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011). He is a co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by Charta.